- Employment has been resilient to inflation, rising rates and slowing growth trends, but for how much longer?

- Consumer financial situations have been impacted, reducing savings rates and increasing borrowing levels…

- Factors to help the economy regain its footing may not be helpful for the U.S. consumer in the near term…

For context, let’s quickly walk the path of 2022. Q1 was about the Fed embarking on its inflation battle against a strong economy. Unfortunately, this was at the expense of an equity market revaluation. But looking back, nothing there should be surprising. Moving into Q2 is where things got tricky. We started to observe the signs of slowing economic activity, purposely caused by the Federal Reserve to combat the excessive inflation that has been built up post-pandemic, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.

Manufacturing surged post-pandemic as consumers tried to get their hands on seemingly anything available. This pushed the ISM Manufacturing index to its highest level on record. Supply disruptions bottlenecked the economy, limiting goods availability and pushing up prices in the process. Consumers made a preference shift in the first half of 2021. The manufacturing surge peaked in Q1 ’21. The Non-Manufacturing index rose substantially from there, peaking itself late in Q4 of ‘21. Since then, both sides of the economy have experienced meaningful slowdowns as we head into the second half of 2022.

(Source; Bloomberg, 12/31/99 – present) Measures of both goods and services have slowed from all-time highs this year due to higher costs and lower demand. Both remain in growth territory but are subject to the risk of a further slowdown in consumer spending.

To be sure, economic activity had reached multi-decade high levels in 2021, so a slowdown brings us back to a still moderate pace of activity. But the rate hikes have had an impact on demand, for sure. As we slide into the second half of 2022, the pretext has changed somewhat to concerns of a U.S. recession. A lot of what happens rests on the shoulders of the consumer so it only makes sense to frame the picture of where the U.S. consumer stands and what variables may change that for the better or worse.

Employment picture

The unemployment rate is historically low, exceedingly low also considering the slowdown in growth. Job openings, as measured by the JOLTS survey, are way above any figures from history prior to the pandemic, even after a dip in July. The U.S. worker has had the most control over the labor market as they have had in years. Employers across industries are having difficulty finding workers.

There are some dynamics in place in the US labor market that are beyond the scope here (gig workers, remote work post-pandemic and structural employment shifts). But for the sake of this discussion, employment had/has been strong, even as the economy has pulled off the gas. One of the curious juxtapositions is how strong the labor market has been considering the slowdown we have experienced (as of this writing, we got our second consecutive negative GDP print). Going back in the annals (at least to the 1960s), the U.S. economy has never experienced a period of two negative growth quarters WITHOUT having negative non-farm payroll print during or proceeding it.

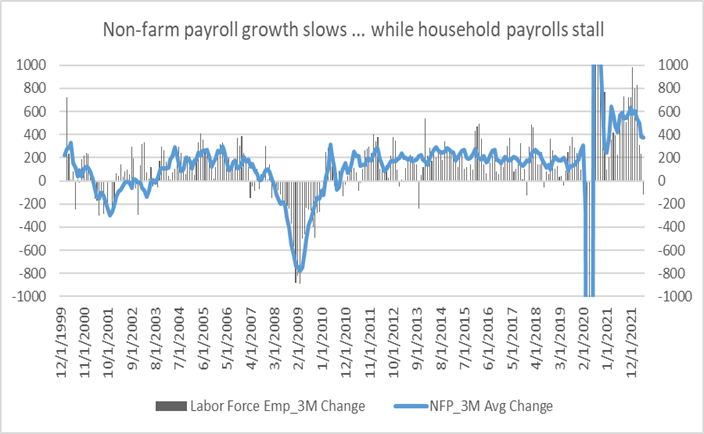

Initial jobless claim levels are still historically good in the 250k range, but it is worth noting they have risen from the 170k range in late Q1. U.S. non-farm payrolls continue to post growth above 300k/month, with an unexpected blowout number above 500k in July. However total U.S payrolls as measured by the BLS has slowed near the flat line since peaking in March as well.

(Source; Bloomberg, 12/31/-99 – present) Non-farm employment gains have remained strong, especially at this level of unemployment and slowdown in growth. Three months moving average of change in total labor force count (measured by the BLS), a little more volatile than pure changes in non-farm, has turned negative.

Employers are having a hard time attracting workers, so the last thing they want to do is let them go unless absolutely critical. Hiring and training new employees is costly. Which all could mean employers would be willing to let labor costs eat more into margins than normal. While employers may be less willing to let go of workers, the pace of hiring can slow.

Consumer Health

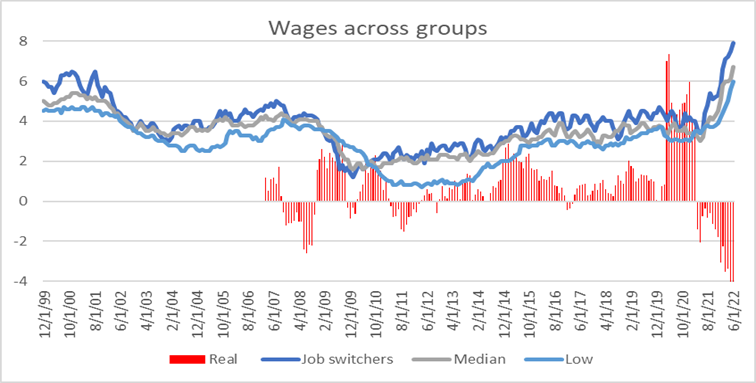

The employment situation has been solid and nominal wages have increased substantially across most income distributions. Median wages have increased almost 7 percent YoY, faster than any period in the data set. Job switchers have seen the greatest increase, which backs up the logic that employers are having to pay up for new talent. Another positive sign is that low-wage workers have seen the biggest YoY wage increase on record as well. The problem is that inflation has eaten into income, pushing real wage growth down almost -4.5 percent YoY.

(Source; Bloomberg) All classifications of wages have seen substantial increases over the past year. Unfortunately, the gains have not outpaced inflation, resulting in negative real wage growth.

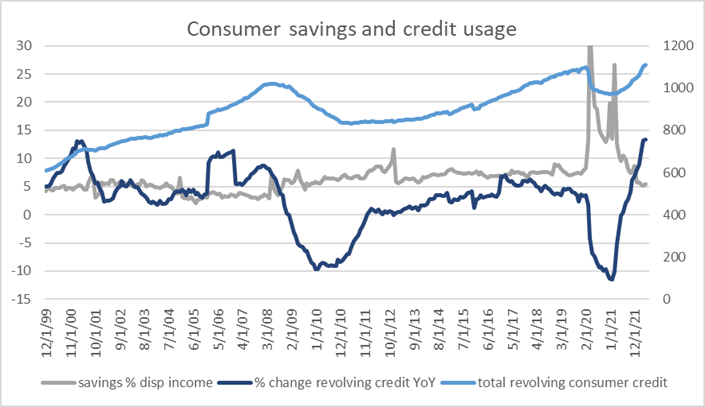

While incomes have increased, expenses have more than kept up, which is starting to impact consumer purchasing habits. Savings as a % of disposable income has plummeted in the past year near the lowest levels post-financial crisis. Rising costs have severely increased household expenses. At the same time, the use of revolving credit has accelerated, above the levels that proceeded two major economic downturns this century. To be sure, after declining by over 10 percent after the beginning of the pandemic, the total outstanding revolving credit balance is above the pre-pandemic level. During the early days of the pandemic, consumers were more cash-flush from the combination of government programs and the lack of spending on services (i.e.; eating out, travel, etc..). The end of social programs and accommodative rate policy as well as higher costs for goods and services has reversed the trend in savings and revolving credit.

(Source; Bloomberg) Consumer savings as a % of disposable income surged after the pandemic. That has slowed to the lowest level in a decade…while revolving credit usage has increased, specifically over the last year as expenses have ballooned.

If we were to make the assumption that the labor market is somewhat resilient to a decline in economic growth, what type of stamina does that consumer have to stay resilient in the face of no stimulus, higher borrowing costs and higher costs for goods?

In Walmart’s Q2 earnings report, they mentioned the consumer spending focus was moving back toward necessities. In addition, markdowns were necessary to work off inventory. Which is interesting as Walmart has what might be considered the best gauge of consumer activity, especially in the staples and lower-end discretionary markets. Could this be a harbinger that supply chains are catching up to demand? That would be helpful from the inflation front, but a clear sign of slowing demand, meaning the Fed cuts are having an impact.

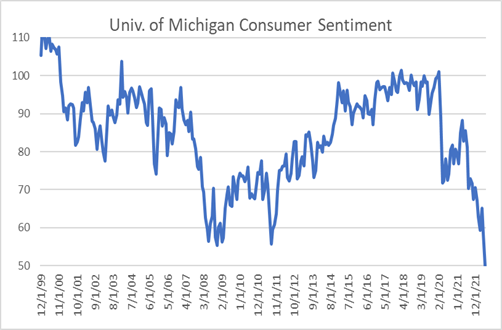

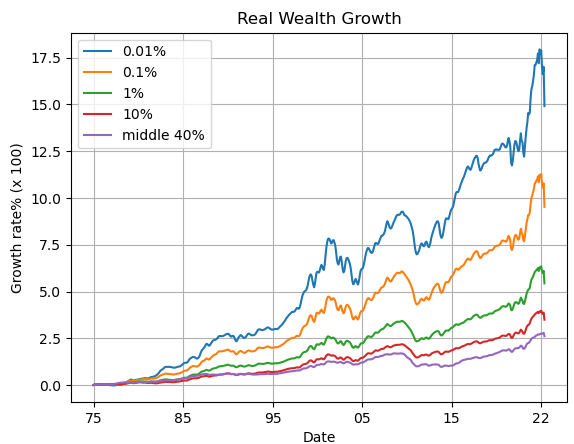

Last, there’s the thing of sentiment. The University of Michigan consumer sentiment gauge has been plummeting for the past year and a half, to the lowest levels on record (below the financial crisis and Covid-onset lows). It’s hard to believe sentiment can be undone to this level so quickly, but if we look at growth in Real Wealth, the market losses and negative wage growth might be causing a double whammy.

Source; Bloomberg, 12/31/99 – present

Source; Realtimeinequality.org, 1975 – present

High inflation and lower stocks tend to do that. Sentiment figures this low might feel ripe for mean-reversion. Better inflation data should help ease the pain, but if the labor markets experience more weakness, how good will the consumer feel about spending more for goods and services?

Summary

What can we expect from the consumer moving forward? The best-case scenario is inflation abates substantially for the rest of this year and into 2023. This would give the consumer a breather in the expenses department, also allowing the economy to regain its footing. It could also mean the Fed would reduce its objective for terminal interest rates.

Unfortunately, it appears the economy does need more of a slowdown to achieve a better supply-demand balance that would impact the consumer. With the unemployment rate at 3.6 percent, the marginal contribution from new labor is slowing. The labor force participation rate has recovered most of its losses from the pandemic, at least in the 16-24 and 25-55 age ranges. If we were to recover the last 1 percent or so, that could equate to another 1.5m workers or so at this UE rate. Inflation has abated from its peak but still remains stubbornly high. The Fed looks committed to the task of achieving higher terminal rates (than current). A recession to reset everything from stocks to the consumer may be what’s needed.

Astor Investment Management LLC is a registered investment adviser with the SEC. All information contained herein is for informational purposes only. This is not a solicitation to offer investment advice or services in any state where to do so would be unlawful. Analysis and research are provided for informational purposes only, not for trading or investing purposes. All opinions expressed are as of the date of publication and subject to change. They are not intended as investment recommendations. These materials contain general information and have not been tailored for any specific recipient. There is no assurance that Astor’s investment programs will produce profitable returns or that any account will have similar results. You may lose money. Past results are no guarantee of future results. Please refer to Astor’s Form ADV Part 2A Brochure for additional information regarding fees, risks, and services.

The Astor Economic Index®: The Astor Economic Index® is a proprietary index created by Astor Investment Management LLC. It represents an aggregation of various economic data points. The Astor Economic Index® is designed to track the varying levels of growth within the U.S. economy by analyzing current trends against historical data. The Astor Economic Index® is not an investable product. The Astor Economic Index® should not be used as the sole determining factor for your investment decisions. The Index is based on retroactive data points and may be subject to hindsight bias. There is no guarantee the Index will produce the same results in the future. All conclusions are those of Astor and are subject to change. Astor Economic Index® is a registered trademark of Astor Investment Management LLC.

MAS-M-291338-2022-08-04